John II of France

| John II | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Portrait of John painted on wood panel around 1350, Louvre Museum | |

|

|

|

| Reign | 22 August 1350 – 8 April 1364 |

| Coronation | 26 September 1350, |

| Predecessor | Philip VI |

| Successor | Charles V |

| Spouse | Bonne of Bohemia Joan I, Countess of Auvergne |

| Issue | |

| Charles V of France Louis I of Naples John, Duke of Berry Philip II, Duke of Burgundy Joan, Queen of Navarre Isabella, Countess of Vertus |

|

| House | House of Valois |

| Father | Philip VI of France |

| Mother | Joan of Burgundy |

| Born | 16 April 1319 Le Mans, France |

| Died | 8 April 1364 (aged 44) Savoy Palace, London, England |

| Burial | Saint Denis Basilica |

John II (16 April 1319 – 8 April 1364), called John the Good (French: Jean le Bon), was the King of France from 1350 until his death. He was the second sovereign of the House of Valois and is perhaps best remembered as the king who was vanquished at the Battle of Poitiers and taken as a captive to England.

The son of Philip VI and Joan the Lame, John became the Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, and Duke of Normandy in 1332. He was created Count of Poitiers in 1344, Duke of Aquitaine in 1345, and Duke of Burgundy (as John I) from 1361 to 1363. By his marriage to Joanna I, Countess of Auvergne and Boulogne, he became jure uxoris Count of Auvergne and Boulogne from 1350 to 1360.

John succeeded his father in 1350 and was crowned at Notre-Dame de Reims. As king, John surrounded himself with poor administrators, preferring to enjoy the good life his wealth as king brought. Later in his reign, he took over more of the administration himself.

Contents |

Early life

John was nine years old when his father had himself crowned as Philip VI of France. His ascent to the throne was unexpected, and because all female descendants of his uncle Philip the Fair were passed over, it was also disputed. The new king had to consolidate his power in order to protect his throne from rival claimants. Philip therefore decided to marry off his son John—then thirteen years old—quickly to form a strong matrimonial alliance, at the same time conferring upon him the title of Duke of Normandy.

Thought was initially given to a marriage with Eleanor, sister of the King of England, but instead Philip invited John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, to Fontainebleau. Bohemia had aspirations towards Lombardy and needed French diplomatic support. A treaty was drawn up. The military clauses stipulated that in the event of war Bohemia would support the French army with four hundred infantrymen. The political clauses ensured that the Lombard crown would not be disputed if the King of Bohemia managed to obtain it. Philip selected Bonne of Bohemia as a wife for his son as she was closer to child-bearing age (16 years), and the dowry was fixed at 120,000 florins.

Marriage with Bonne of Bohemia

John came of age on 26 April 1332, and received overlordship of the duchy of Normandy, as well as the counties of Anjou and Maine. The wedding was celebrated on 28 July at the church of Notre-Dame in Melun in the presence of six thousand guests. The festivities were prolonged by a further two months when the young groom was finally knighted at the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. Duke John of Normandy was solemnly granted the arms of a knight in front of a prestigious assistance bringing together the kings of Luxembourg and Navarre, and the dukes of Burgundy, Lorraine and the Brabant.

Duke of Normandy

In 1332, John became Duke of Normandy in prerogative, and had to deal with the reality that most of the Norman nobility was already allied with the English camp. Effectively, Normandy depended economically more on maritime trade across the English Channel than it did by river trade on the Seine. The Duchy had not been English for 150 years but many landowners had possessions across the Channel. Consequently, to line up behind one or other sovereign risked confiscation. Therefore the Norman nobility were governed as interdependent clans which allowed them to obtain and maintain charters guaranteeing the duchy a deal of autonomy. It was split into two key camps, the counts of Tancarville and the counts of Harcourt—which had been in conflict for generations[1].

Tension arose again in 1341. The king, worried about the richest area of the kingdom breaking into bloodshed, ordered the bailiffs of Bayeux and Cotentin to quell the dispute. Geoffroy d' Harcourt raised troops against the king, rallying a number of nobles protective of their autonomy and against royal interference. The rebels demanded that Geoffroy be made duke, thus guaranteeing the autonomy granted by the charter. Royal troops took the castle at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte and Geoffroy was exiled to the Brabant. Three of his companions were decapitated in Paris on 3 April 1344[2].

By 1345 increasing numbers of Norman rebels had begun to pay homage to Edward III, constituting a major threat to the legitimacy of the Valois kings. The defeat at Crécy and the rendering of Calais further damaged royal prestige. Defections by the nobility increased—particularly in the north and west whose land fell within the broad economic influence of England. Consequently the French king decided to seek a truce. Duke John met Geoffroy d' Harcourt, to whom the king agreed to return all confiscated goods; even appointing him sovereign captain in Normandy. John then approached the Tancarville which represented the key clan whose loyalty could ultimately ensure his authority in Normandy. The marriage of John, Viscount of Melun to Jeanne, the only heiress of the county of Tancarville ensured the Melun-Tancarville party remained loyal to John the Good, while Godefroy de Harcourt continued to act as defender for Norman freedoms and thus of the reforming party[3].

Treaty of Mantes and Battle of Poitiers

In 1354, John's son-in-law and cousin, Charles II of Navarre, who, in addition to his small Pyrenean kingdom, also held extensive lands in Normandy, was implicated in the assassination of the Constable of France, Charles de la Cerda. Nevertheless, in order to have a strategic ally against the English in Gascony, on 22 February 1354, John signed the Treaty of Mantes with Charles. The peace did not last between the two and Charles eventually struck up an alliance with Henry of Grosmont, the first Duke of Lancaster. The next year (1355), John signed the Treaty of Valognes with Charles, but this second peace lasted hardly longer than the first. In 1355, the Hundred Years' War flared up again.

In July of 1356, The Black Prince, son of Edward III of England, took a small army on a chevauchée through France. John pursued him with an army of his own. In September a few miles southeast of Poitiers, the two forces met.

John was confident of victory—his army was probably twice the size of his opponent's—but he did not immediately attack. While he waited, the papal legate went back and forth, trying to negotiate a truce between the leaders. There is some debate over whether the Prince wanted to fight at all. He offered his wagon train, which was heavily loaded with loot. He also promised not to fight against France for seven years. Some sources claim that he even offered to return Calais to the French crown. John countered by demanding that 100 of the Prince's best knights surrender themselves to him as hostages, along with the Prince himself.

No agreement could be reached. Negotiations broke down, and both sides prepared for combat.

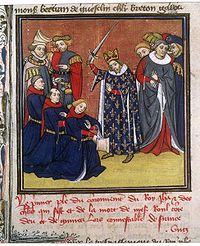

On the day of the Battle of Poitiers, John and 19 knights from his personal guard dressed identically. This was done to confuse the enemy, who would do everything possible to capture the sovereign on the field. In spite of this precaution John was captured. Though he fought with valor, wielding a large battle-axe, his helmet was knocked off. Surrounded, he fought on until Denis de Morbecque, a French exile who fought for England, approached him.

"Sire," Morbecque said. "I am a knight of Artois. Yield yourself to me and I will lead you to the Prince of Wales."

King John surrendered by handing him his glove. That night King John dined in the red silk tent of his enemy. The Black Prince attended to him personally. He was then taken to Bordeaux, and from there to England. Although Poitiers is centrally located, it is not known that anyone—noble or peasant—attempted to rescue their king.

While negotiating a peace accord, he was at first held in the Savoy Palace, then at a variety of locations, including Windsor, Hertford, Somerton Castle in Lincolnshire, Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire and briefly at King John's Lodge, formerly known as Shortridges, in East Sussex. A local tradition in St Albans is that he was held in a house in that town, at the site of the 15th-century Fleur de Lys inn, before he was moved to Hertford. There is a sign on the inn to that effect, but apparently no evidence to confirm the tradition.[4] Eventually, John was taken to the Tower of London.

Prisoner of the English

As a prisoner of the English, John was granted royal privileges, permitting him to travel about and to enjoy a regal lifestyle. At a time when law and order was breaking down in France and the government was having a hard time raising money for the defence of the realm, his account books during his captivity show that he was purchasing horses, pets, and clothes while maintaining an astrologer and a court band.

The Treaty of Brétigny (1360) set his ransom at 3 million crowns. Leaving his son Louis of Anjou in English-held Calais as a replacement hostage, John was allowed to return to France to raise the funds.

But all did not go according to plan. In July of 1363, King John was informed that Louis had escaped. Troubled by the dishonour of this, and the arrears in his ransom, John did something that shocked and dismayed his people: he announced that he would voluntarily return to captivity in England. His council tried to dissuade him, but he persisted, citing reasons of "good faith and honour." He sailed for England that winter and left the impoverished citizens of France again without a king.

John was greeted in London 1364 with parades and feasts. A few months after his arrival, however, he fell ill with an "unknown malady." He died at the Savoy in April 1364. His body was returned to France, where he was interred in the royal chambers at Saint Denis Basilica.

Personality

John suffered from fragile health. He engaged little in physical activity, practised jousting rarely, and only occasionally hunted. Contemporaries report that he was quick to get angry and resort to violence, leading to frequent political and diplomatic confrontations. He enjoyed literature, and was patron to painters and musicians.

The image of a "warrior king" probably emerged from the courage in battle he showed at Poitiers, and the creation of the Order of the Star. This was guided by political need as John was determined to prove the legitimacy of his crown–particularly as his reign, like that of his father, was marked by continuing disputes over the Valois claim from both Charles II of Navarre and Edward III of England. From a young age, John was called to resist the de-centralising forces which impacted upon the cities and the nobility; each attracted either by English economic influence or the reforming party. He grew up amongst intrigue and treason, and in consequence he governed in secrecy only with a close circle of trusted advisers.

He took as wife Bonne of Bohemia, and fathered 10 children, in eleven years. Some historians[5] also suggest a strong romantic and possibly homosexual attachment to Charles de la Cerda. La Cerda was given various honours and appointed to the high position of connetable when John became king; he accompanied the king on all his official journeys to the provinces. La Cerda's rise at court excited the jealousy of the French barons, several of whom stabbed him to death in 1354. As such, La Cerda's fate paralleled that of Edward II of England's Piers Gaveston in England, and John II of Castile's Alvaro de Luna in Spain; the position of a royal favourite was a dangerous one. John's grief on La Cerda's death was overt and public.

Ancestry

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family and children

On 28 July 1332, at the age of 13, John was married to Bonne of Bohemia (d. 1349), daughter of John I (the Blind) of Bohemia. Their children were:

- Charles V (21 January 1338–16 September 1380)

- Louis I, Duke of Anjou (23 July 1339–20 September 1384)

- John, Duke of Berry (30 November 1340–15 June 1416)

- Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (17 January 1342–27 April 1404)

- Joan (24 June 1343–3 November 1373), married Charles II (the Bad) of Navarre

- Marie (12 September 1344–October 1404), married Robert I, Duke of Bar

- Agnes (1345–1349)

- Margaret (1347–1352)

- Isabelle of Valois (1 October 1348–11 September 1372), married Gian Galeazzo I, Duke of Milan

On 19 February 1350, at Nanterre, he married Joanna I of Auvergne (d. 1361), Countess of Auvergne and Boulogne. She was the widow of Philip of Burgundy, the deceased heir of that duchy, and mother of the young Philip I, Duke of Burgundy (1344–61) who became John's stepson and ward. John and Joanna had two daughters, both of whom died young:

- Blanche (b. 1350)

- Catherine (b. 1352)

He was succeeded by his son, Charles V.

External links

References

|

John II of France

House of Valois

Cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty

Born: 16 April 1319 Died: 8 April 1364 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Philip VI |

King of France 22 August 1350 – 8 April 1364 |

Succeeded by Charles V |

| French royalty | ||

| Preceded by Philip, Count of Valois |

Heir to the Throne as heir apparent 29 May 1328 – 22 August 1350 |

Succeeded by Charles, Dauphin of France |

| French nobility | ||

| Preceded by Joanna I |

Count of Auvergne and Boulogne 13 February 1350 – 29 September 1360 with Joanna I |

Succeeded by Philip of Rouvres |

| Preceded by Philip of Rouvres |

Duke of Burgundy as 'John I' 1361–1363 |

Succeeded by Philip the Bold |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)